Last month I travelled to Vukovar, a town in eastern Croatia that in 1991 became known as Europe’s Stalingrad after Serb forces first pulverised the town with planes and artillery and then machine-gunned hundreds of the injured survivors. I found that ethnic hatred and resentment is still very much alive.

With Donald Trump in the White House and a new zeitgeist abroad nationalist sentiment in the Balkans is once again stirring. This week I am in Bosnia where the Serb leader Milorad Dodik, egged on by Belgrade and Moscow, is pushing for secession.

The Yugoslav wars of the 1990s were my first big assignment as a young reporter and I ended up covering them for nearly a decade. Well over 100,000 died and millions of lives were uprooted. I just hope that history is not coming full circle.

At first blush there is little remarkable about this town of 23,000 at the far eastern end of the crescent that is modern-day Croatia.

From the west it is reached along a road through ploughed fields with tractors working in the spring sunshine. On the eastern end it is bracketed by an old water tower flying the Croatian flag.

In the main square locals gather in cafes and eateries to order cevapcici - small sausages made of minced meat that are a staple throughout what was once Yugoslavia - and sugary drinks.

But 30 years ago, for two terrible months, the fate of this town topped news bulletins around the world as the Yugoslav National Army, then the fourth largest in Europe, working in cahoots with Serb nationalist volunteers, pounded its defenders into submission.

When Croatian forces finally withdrew, walking through the night to avoid snipers and artillery, they left behind nearly 900 dead comrades. More than a thousand civilians also died in the fighting and upwards of 1,100 Serb soldiers and paramilitaries.

The Serb forces then moved in, rounded up more than 260 of the injured, took them to a nearby collective farm, and machine-gunned them. At least 60 are still missing.

Far worse was to follow later in the Bosnian war to the south – the Serbs machine-gunned 8,000 men after the fall of Srebrenica in 1995 - but at the time the mass execution at Vukovar was one of the worst war crimes committed in Europe since World War 2.

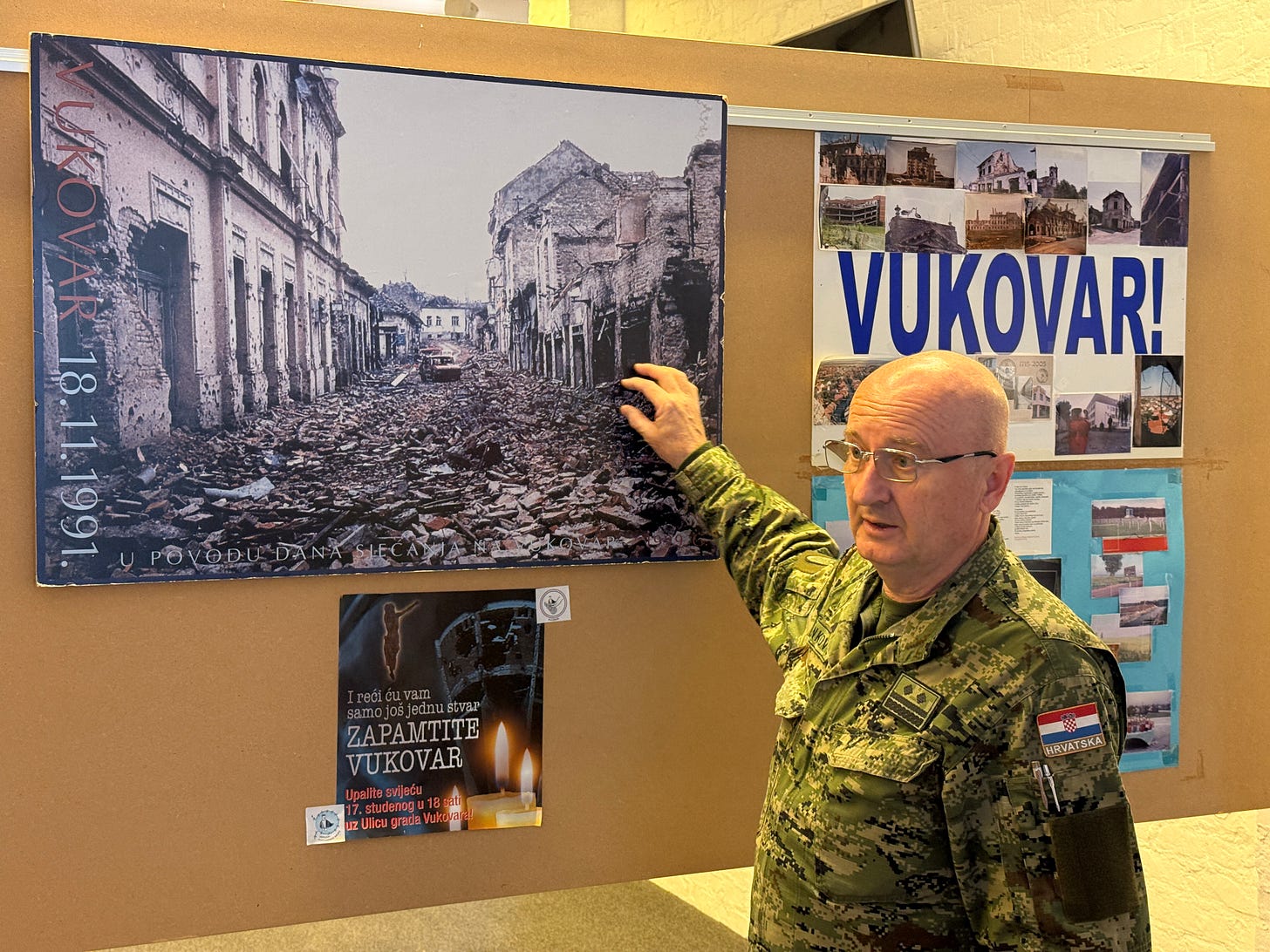

Ivan Marinkovic, who fought with the Croatian army and today guides visitors around a memorial centre set up to commemorate the battle, remembers his night-time escape with 47 of his colleagues.

"In wartime your body runs at 1000 Hz" he said: "Even so it took us 45 hours to get to safety - a journey that would normally take 45 minutes on a bike."

Four years later, as the Serb forces that once held a third of Croatia were in retreat, a deal was brokered that gave the town back to Zagreb.

In many ways today Vukovar, with a population that is still 30 percent ethnic Serb, has become the cornerstone of modern Croatian identity.

Every schoolchild in the country is brought here for three days to visit the memorial centre which shows maps, artefacts, old military equipment, detention facilities and photos of men disfigured by gunshot and mine blast injuries.

A large new hostel has even been built to house the young visitors, who are also taken to Ovcara, 10 minutes drive outside Vukovar where the injured Croat soldiers were machine-gunned.

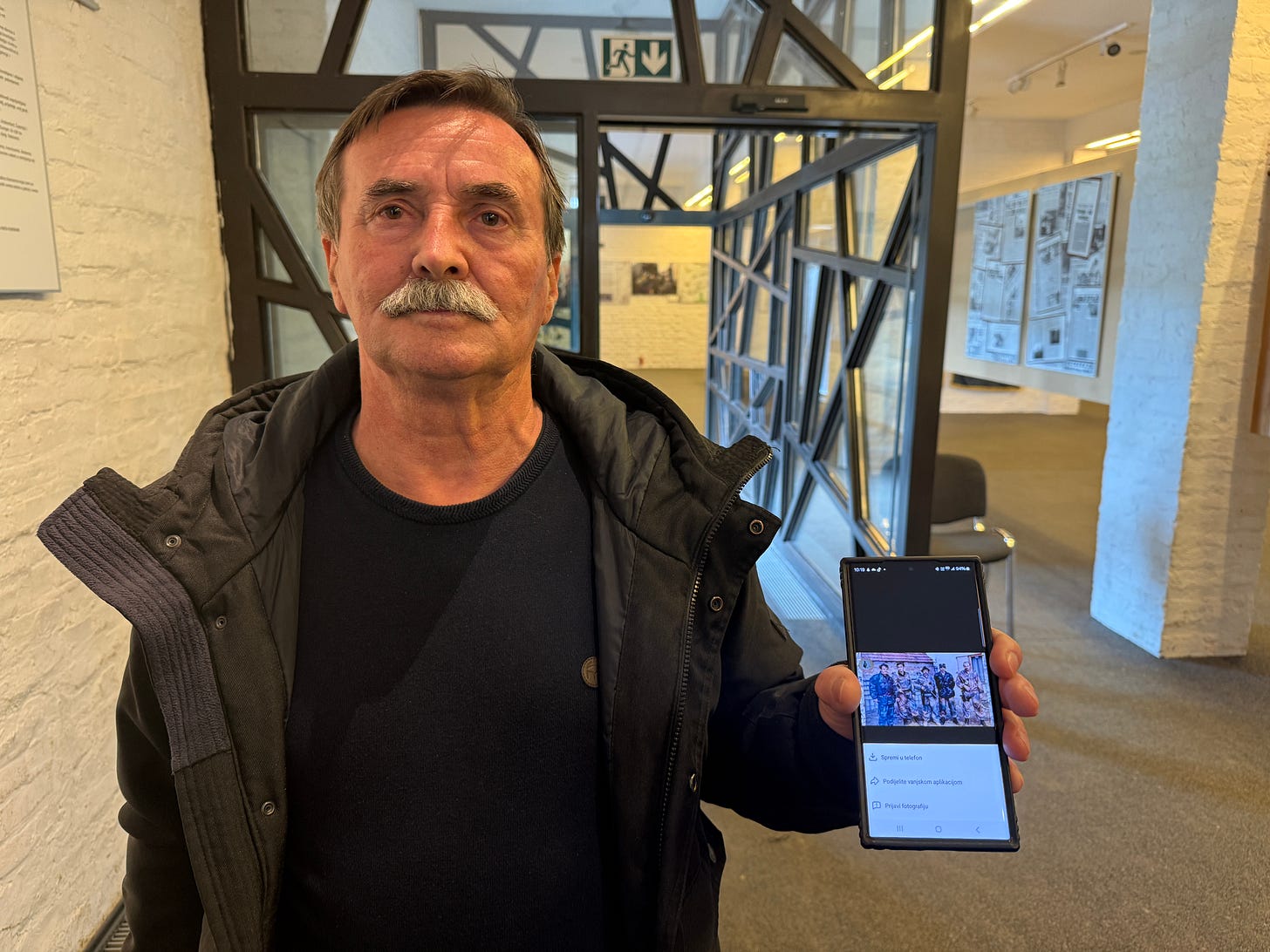

Ivan Andjelic, a 69 year-old war veteran who went by the call sign 'doctor' and has had movies made about his exploits, said: "I don't hate anyone. But Serbs always thought this was their colony. They attacked us. They wanted a Greater Serbia."

Last weekend Vukovar was the picture of calm. But beneath the surface inter-ethnic tensions still simmer and there appears to have been little local reconciliation.

At a petrol station in the small village of Trpinje on the road in from the west, which is 95 percent ethnic Serb, Vanya, 29, was working the till.

"Relations are not good," she said. "I have no Croat friends. My parents fought in the war and the war is still in our heads. That will never change."

At a small table Dragan, 57, a Serb who mostly works in Switzerland, was drinking coffee and smoking. "The Croats are like the Germans and the Ukrainians," he said. "They are all fascists and they will hate us for 300 years."

On the streets of Vukovar itself, there are few signs left of the war. Almost all the buildings have been rebuilt.

In one central pedestrian street, which was a field of rubble at the end of 1991 today there a smart flagstones, a shop selling the merchandise of the local football club - named Vukovar 1991, and a pub, also named after the town.

But elsewhere in the Balkans tensions are rising again. Authorities have issued an arrest warrant for Milorad Dodik, the leader of the Serb half of Bosnia which is threatening to secede.

And, even in Croatia, hatred and resentment is just below the surface.

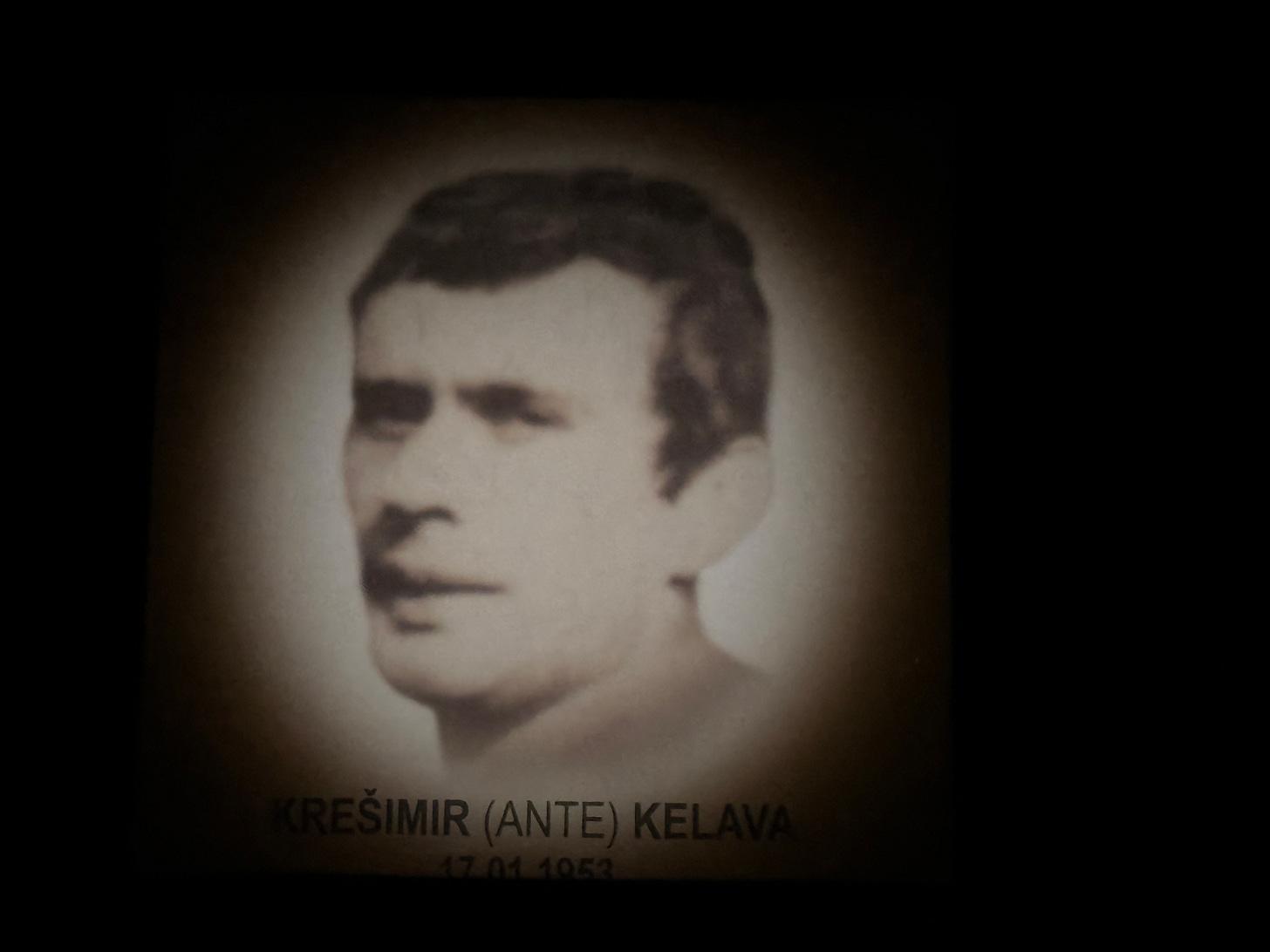

When we talked to two middle-aged sisters, Maya and Silva, who were 14 and 15 at the time of the battle, they said their father was among those who was dragged from the hospital, taken away, and shot.

"I can't describe how I feel," Maya said. "We lost our Dad. And some of the Serbs that committed the crimes are still living here. It's offensive."

.At the Ovcara memorial we sought out the ladies' father, a man with a thick mane of hair called Kresimir Kelava. Along with the other victims his likeness had been rendered on a piece of glass in a large dark room.

"I can't forgive. It doesn't matter how much time passes," Silva said

After the massacre, the Serb militias took Belgrade-based Western correspondents to their killing fields near Vukovar. 'Look,' they said, pointing to their Croatian victims. 'These men are all Serbs and were murdered by the Croats'

The lie was transparent. The correspondents were not fools

The horrible Donald said that the Ukraine war wouldn’t have started if he had been President. You can guarantee that if this one starts again, he’ll say it’s nothing to do with America and allow Russian proxies to roll over the Croatians